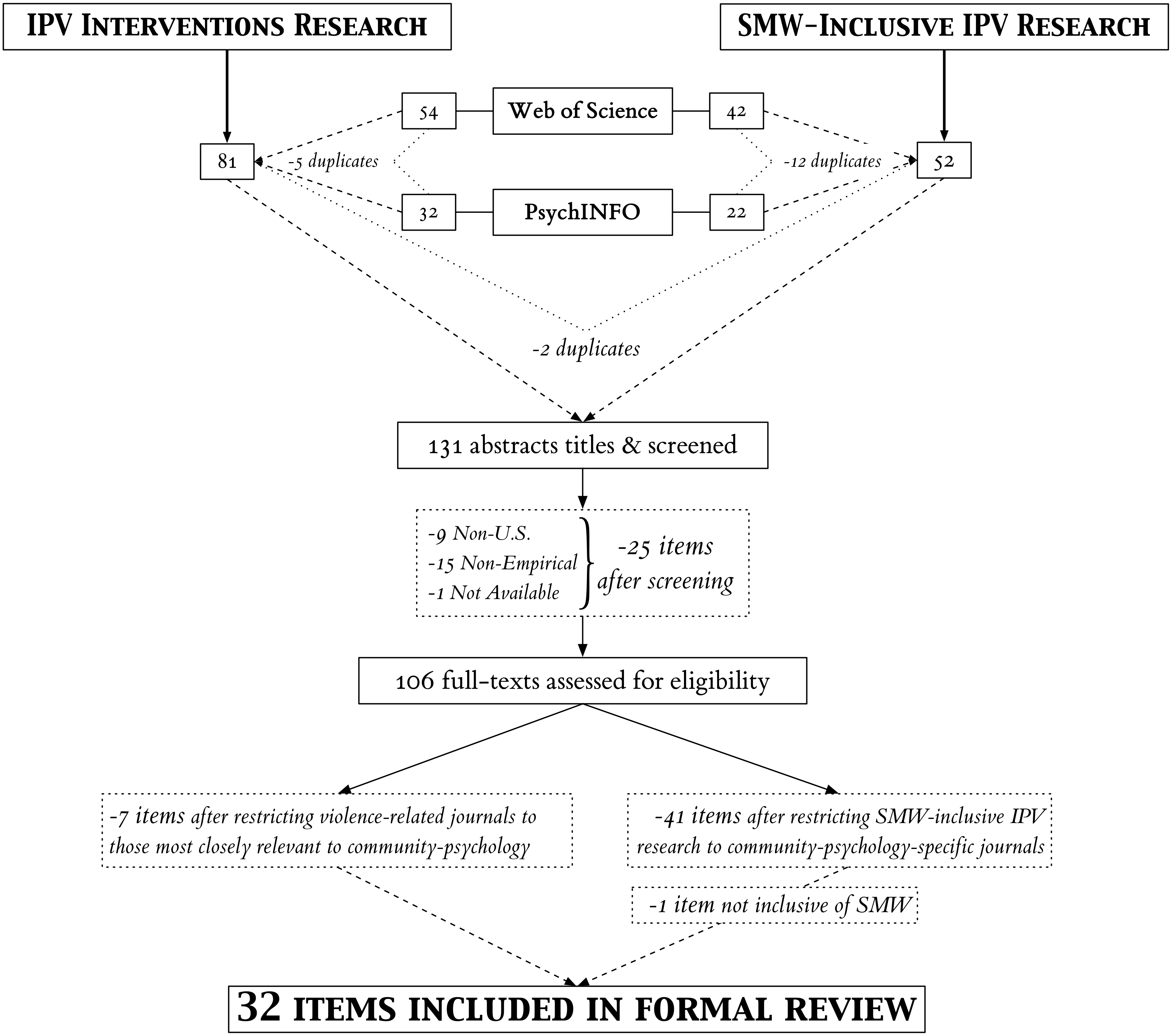

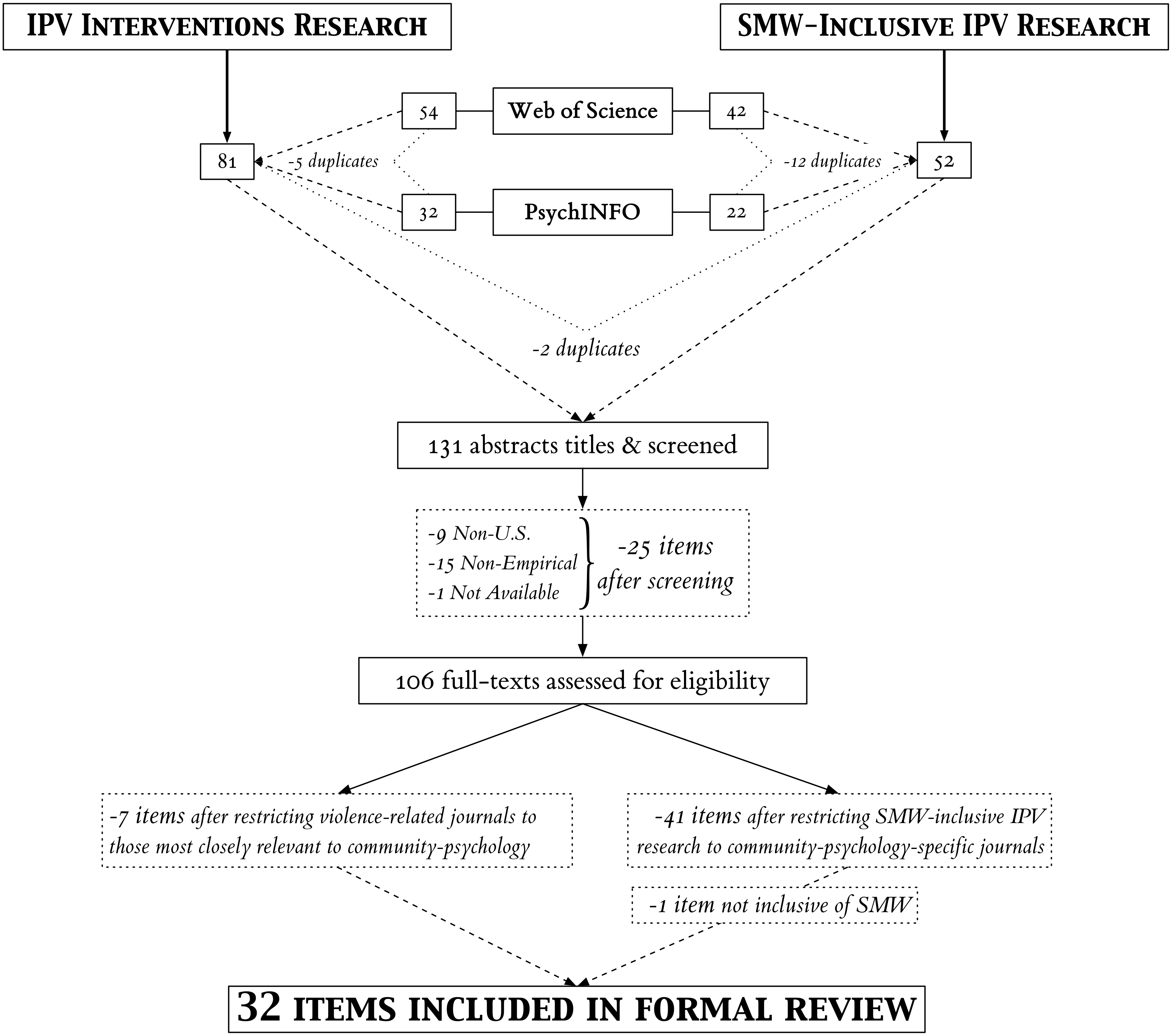

Flow-chart of systematic literature database search results and decisions for inclusion and exclusion in formal review“

Six separate literature searches were conducted using the PsycINFO (PI) and Web of Science (WoS) online citation indexing databases via the Portland State University library website:

1. IPV - General

2. IPV Interventions

3. IPV Intervention Evaluations

4. Female Same-Sex/Same-Gender IPV (FSSIPV) - General

5. FSSIPV Interventions

6. FSSIPV Intervention Evaluations

Because this review is not intended to provide a cross-national examination of IPV interventions research, I restricted each of the above literature searches to empirical studies conducted within the United States and published between 1965 and 2017 (i.e., the year of the Swampscott conference and the present year; Fryer, 2008). In addition, to focus the review around community psychology theoretical and methodological frameworks, I initially confined the search results to articles published in scholarly peer-reviewed journals specific to Community Psychology. The list of Community Psychology journals, provided in Table 2, included The American Journal of Community Psychology and additional publications endorsed by the Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA) as closely related to community psychological research (The Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA), 2017). This restriction yielded a limited number of empirical articles specific to intimate partner violence interventions in general, and yielded zero (0) IPV intervention-related studies specifically inclusive of sexual minority women. In response to this initial finding, I re-ran the first database search listed above (labeled as “IPV - General”) using the same keywords, publication year range, and location restrictions as before, but omitting the previously-imposed constraints on the journal title parameter. Then, taking advantage of of the various data points provided along with the primary sources returned from a given search in the both PsycINFO and Web of Science databases, I extracted tabulated data comprised of the journal title of each article in the results list and the total number of articles returned from each of those journals for the latter database search’s results.

Based on (a) the volume of IPV-related literature published by each journal and (b) the alignment of the topical and methodological foci with community psychological principles and values, I selected the following four violence-related journals to be added to the list of specified publications in the database searches: (1) Journal of Interpersonal Violence, (2) Journal of Family Violence, (3) Violence Against Women, and (4) Violence and Victims. I then re-ran each of the six database searches with the publication title parameter restricted to any of the community-psychology-specific journal titles listed in Table 2 or any of these four violence-specific publications (see Table 3).

| Database Searcha | \(Range_{N_{Results}}\) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1. | IPV - General | 3,376, 4,386 (PI) |

| 2. | — Interventions | 337, 686 (WoS) |

| 3. | — Intervention Evaluations | 32, 46 (WoS) |

| 4. | Female Same-Sex/Same-Gender IPV - General | 18, 34 (WoS) |

| 5. | — Interventions | 0, 4 (WoS) |

| 6. | — Intervention Evaluations | 0, 2 (WoS) |

Note:

a For each database search, multiple search terms were included for the subject/keywords parameters to represent intimate partner violence

Collectively, the six database searches yielded 106 journal articles after removing duplicates (see Table 1). This selection of empirical research constitutes a community-psychology-focused subset of the available U.S.-based IPV-related literature. Among the initial set of 106 articles, ≈ 35.8% (38) present IPV-related research focused on intervention and/or prevention approaches, programs, and evaluations; however, the majority of this research is not inclusive of sexual minority women. Conversely, the remaining 66 articles consist of IPV-related research specifically inclusive of sexual minority women; however, does not directly concern IPV intervention or prevention approaches. Rather, this latter category of research primarily focuses on the prevalence, causal antecedents, risk factors, correlates, and/or consequences of IPV among sexual minority women and LGBTQ populations in general.

The six database searches were intentionally designed to successively narrow the search results from IPV-related research in general (regardless of focal population(s)) to IPV-related intervention and/or prevention research specific to sexual minority women. Correspondingly, the literature obtained from these database searches was reviewed through a deductive analytic procedure conducted in two phases: (1) initial screening, assessment, and data organization to determine which articles to include in the formal review; and (2) systematic review and methodological evaluation of the literature retained from the first analytic phase of the literature. Both analytic phases were achieved using the R Statistical Programming Language and Environment, the RQDA and RSQLite R packages, and relational databases built and managed using Structured Query Language (SQL; details regarding specific R packages used in conducting analyses and presenting this review are provided in Appendix B; R Core Team, 2016).

Each of the 106 articles returned from the database searches was assessed according to three successive levels of inclusion criteria. The first and most basic inclusion criterion is that the articles must present U.S.-based empirical research. Second, the content of each article should be directly applicable to intimate partner violence interventions (e.g., intervention program development, implementation, and evaluation research; applied community-based research methods; etc.). To assess the second criterion, I coded each article using keywords from the authors’ description of substantive research topics covered. This information was obtained by first examining each article’s title and, if available, abstract or keywords list; and then reviewing the stated purposes, research questions, or hypotheses provided in the main body of each article. The latter step was done to ensure that the coding of each article’s focal research topics was both accurate and comprehensive, as this coding was subsequently used as a “filter” for excluding articles not relevant to IPV interventions. Specifically, I examined the list of codes generated from this process (see codes listed under the “Research Topic” category in Table 4) and selected the following codes that fit within the scope of this review’s previously-described goals and research questions:

Finally, a particularly crucial inclusion criteria for literature obtained from the fourth through sixth database searches (see Table 1) is that the presented research must include sexual minority women as a focal population. For example, among the two empirical research articles returned from the fifth and sixth literature searches, which targeted SMW-inclusive IPV intervention and prevention research (see Table 1), one examined male and female college students’ perceptions of the prevalence of IPV perpetration among their peers (Witte, Mulla, & Weaver, 2015), and the other detailed an item-response theory approach to measuring teens’ attitudes about dating violence among heterosexual adolescents (Edelen, McCaffrey, Marshall, & Jaycox, 2009). While both of these studies somewhat reflect research aligned with community psychological values and methods, their substantive foci failed to meet this review’s inclusion criteria for articles returned from the three database searches specific to sexual minority women.

Any articles not meeting the above-described three levels of inclusion criteria were excluded from remainder of analyses conducted for this review. This initial assessment and filtering analytic phase yielded a final set of 29 empirical studies included in the below-described analyses and later-provided synthesis and methodological critique. Among these studies, 22 are exclusively focused on or applicable only to heterosexual, and typically male-identified, populations; whereas 7 studies are specifically inclusive of female-identified lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, and/or queer groups and individuals (i.e., sexual minority women [“SMW”]).

| Publication Title | \(N_{articles}\) | |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | American Journal of Community Psychology | 1 |

| 2 | American Journal of Preventive Medicine | 1 |

| 3 | American Journal of Public Health | 2 |

| 6 | Journal of Primary Prevention | 1 |

| 9 | Action Research | 0 |

| 10 | American Journal of Health Promotion | 0 |

| 11 | American Journal of Orthopsychiatry | 0 |

| 12 | Australian Community Psychologist | 0 |

| 13 | Community Development | 0 |

| 14 | Community Development Journal | 0 |

| 15 | Community Mental Health Journal | 0 |

| 16 | Community Psychology in Global Perspective | 0 |

| 17 | Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology | 0 |

| 18 | Global Journal of Community Psychology Practice | 0 |

| 19 | Health Education and Behavior | 0 |

| 20 | Health Promotion Practice | 0 |

| 21 | Journal of Applied Social Psychology | 0 |

| 22 | Journal of Community and Applied Social Psychology | 0 |

| 23 | Journal of Community Practice | 0 |

| 24 | Journal of Community Psychology | 0 |

| 25 | Journal of Health and Social Behavior | 0 |

| 26 | Journal of Prevention and Intervention | 0 |

| 27 | Journal of Rural Community Psychology | 0 |

| 28 | Journal of Social Issues | 0 |

| 29 | Psychiatric Rehabilitation Journal | 0 |

| 30 | Psychology of Women Quarterly | 0 |

| 31 | Social Science and Medicine | 0 |

| 32 | The Community Psychologist | 0 |

| 33 | Transcultural Psychiatry | 0 |

| 34 | Progress in Community Health Partnerships | 0 |

| Publication Title | \(N_{articles}\) | |

|---|---|---|

| 4 | Journal of Family Violence | 1 |

| 5 | Journal of Interpersonal Violence | 8 |

| 7 | Violence Against Women | 11 |

| 8 | Violence and Victims | 4 |

The second phase of deductive analysis served to examine the similarities, differences, and anomalies among the set of included articles according to the above-described two categories determined in the previous data reduction and organization process. Following a qualitative comparative analytic (QCA) approach (Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007; Onwuegbuzie & Weinbaum, 2017; Onwuegbuzie, Dickinson, Leech, & Zoran, 2009), I first reviewed each article in its entirety using a literature description and data extraction form (available here) that I created for this project. I developed this form with specific guidance from the systematic literature review and data extraction standards, protocols, templates, and guidelines provided by The PRIMSA Group (Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff, Altman, & The PRISMA Group, 2009) and the Cochrane Collaboration’s resources library and handbook for systematic reviews and meta-analyses (Higgins & Green, 2011). The literature description form consists of sections for recording each reviewed study’s substantive research topic(s) (determined by the stated purpose(s), research question(s), and/or hypotheses, as provided in each article), target population(s)), target population(s), sampling frame setting(s), sampling frame(s), sampling methods, research design (e.g., experimental, cross-sectional, descriptive, etc.), overarching methodology (i.e., qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods), specific data collection methods (e.g., measures, interview questions, archival data sources, etc.), data analytic approaches and procedures, and key findings. The final piece of information included in the form is the ecological levels of analysis involved in a study’s design, methods, and analysis. The ecological levels of analysis section was intentionally placed at the end of the description form so that the author could determine which levels of analysis were involved in each study based on the characteristics of the full array of information and study characteristics recorded in the prior sections of the form. That is, the ecological levels of analysis involved in each of the reviewed studies were inferred based on the other data points recorded in the literature description form for each reviewed study, all of which were directly extracted from the information provided in each article. The summative data across the reviewed studies were then compiled and restructured to form a methodologically-focused codebook, presented in Table 4, consisting of (1) information categories corresponding to the research design and methods-related sections covered in the literature description form, and (2) the codes generated in each information category from the discrete characteristics recorded in the description form across the reviewed studies.

Methodological Review & Evaluation

Research conducted within the subset of community psychology focused around intimate partner violence was initially evaluated according to the level of inclusion and exclusion of the historically marginalized population of particular interest for the purposes of this review: sexual minority women (SMW). The implementation of action-oriented community-psychology methodologies and analytic approaches was then reviewed within each of these categories (i.e., inclusion or exclusion of SMW) in terms of (1) the appropriateness of the methods to the research question(s), (2) how the methods facilitated the inclusion or exclusion of sexual minority women, and (3) whether and how (where applicable) exclusion of sexual minority women is justified.

Defining and Evaluating Methodological Rigor

The notion of “scientific rigor” is particularly important in evaluating a set of applied social science research studies employing varying methodologies. This is because “rigor” is not necessarily clearly defined across methodologies, and some research philosophies do not consider certain methodologies as capable of achieving scientific rigor at all. For the purposes of this review, methodological rigor is broadly defined as the extent to which a given study employs research methods that best address the overarching research question(s) and/or hypothesis/hypotheses, and the quality of the implementation of those methods. This definition of methodological rigor therefore does not prioritize a particular method nor category of methods (e.g., quantitative over qualitative, mixed-methods over single-methods, etc.), but rather prioritizes the choice and implementation of methods employed to address a given study’s purposes. In addition, this definition of methodological rigor allows for more specific and in-depth consideration of the limitations presented, and not presented, in each study’s report.

Rigor in action-oriented community-based research methods was evaluated according to the choice, description, justification, appropriateness, and execution of each reviewed study’s design (i.e., experimental or cross-sectional) and overarching methodology (i.e., quantitative, qualitative, or mixed-methods). Each of these aspects of the reviewed literature was identified in terms of each evaluated study’s purpose, hypotheses, and/or research questions description, sampling frame definition, sampling and data collection methods, analytic approach(es), and description of findings and limitations. Because the underlying goals of this systematic review are motivated by the continued relative absence of sexual minority women in the larger body of IPV-related empirical research literature, especially in terms of IPV perpetrator interventions research, particular attention was given to the sampling frame definitions and sampling methods employed among the empirical studies reviewed here. That is, the evaluated research included in the present review was specifically evaluated in terms of how the methods facilitate the inclusion or exclusion of specific populations, particularly sexual minority women, and whether and how the exclusion of specific populations is justified in each empirical study’s report.

In addition, to assess transparency and reproducibility of the research methods and findings, the overall presentation, dissemination mechanism(s), application, and accessibility of the research was noted where available or applicable. These latter assessments of research transparency and reproducibility also incorporated considerations regarding the incorporation of key and/or distal stakeholders’ input. The accessibility of the research to primary and distal stakeholders would be reflected according to whether and how stakeholders are provided information about and access to reports of a given project’s progress and findings. The role of stakeholder input in the evaluated community-psychology literature was noted in terms of the extent to which efforts made to ensure that all available stakeholders’ and informants’ voices are considered throughout the research process, and that certain voices are not unjustifiably privileged over others. These considerations include evaluation of whether feedback is explicitly solicited, or at least accepted when offered, from key stakeholders and informants to the research, and whether such feedback is genuinely considered by the primary researchers of a given investigation.

| Codes | |

|---|---|

| 1. Research Category | IPV Interventions Research |

| - | LGBTQ-IPV Research |

| 2. Substantive Research Topic | Approach Evaluation |

| - | Bystander Intervention |

| - | Community Capacity |

| - | Coordinated Community Response to IPV |

| - | Help-Seeking |

| - | HIV Intervention/Prevention |

| - | Intervention |

| - | IPV Consequences |

| - | IPV Dynamics |

| - | IPV Intervention Description |

| - | IPV Intervention Development |

| - | IPV Intervention Efficacy |

| - | IPV Intervention Evaluation |

| - | IPV Intervention Proposal |

| - | IPV Perpetrator Interventions |

| - | IPV Prevalance |

| - | IPV Screening |

| - | IPV Victimization Intervention |

| - | Key Stakeholders’ Perspectives |

| - | Macro Contexts of IPV |

| - | Measures |

| - | Outsiders’ Perspective |

| - | Perpetrator Characteristics |

| - | Practitioners’ Perspectives |

| - | Prevention |

| - | Protective Factors |

| - | Public/Program Policy |

| - | Research/Evaluation Methods |

| - | Risk Factors |

| - | System Response |

| - | Victims’/Survivors’ Perspectives |

| 3. Target Population(s) & Sampling Frame | African Americans |

| - | Asian Americans |

| - | At Risk Populations |

| - | Cis-Genders |

| - | College Students |

| - | Couples |

| - | Disabled-Persons |

| - | Females/Women/Girls |

| - | Gender Minorities |

| - | General Population |

| - | Graduate Students |

| - | Heterosexuals |

| - | IPV Intervention Programs |

| - | IPV Perpetrators |

| - | IPV Victims/Survivors |

| - | IPV-Specific Community-Based Practitioners |

| - | Latina/os |

| - | Males/Men/Boys |

| - | Non-IPV Community-Based Practitioners |

| - | Non-IPV Crime Victims |

| - | Non-IPV System Entities |

| - | Not Applicable - Population |

| - | Parents |

| - | Racial Minorities |

| - | Sexual Minorities |

| - | Sexual Minority Women Only |

| - | SMW as Distinct Group |

| - | Urban-Specific Populations |

| - | Youth/Children |

| 4. Sampling Settings | Anger Management Programs |

| - | Archival/Secondary Data |

| - | Childcare Services |

| - | Children’s Services |

| - | CJ - Police |

| - | Colleges/Univeresities |

| - | Community Centers |

| - | Community-Based Services |

| - | Criminal Justice System |

| - | Drug & Alcohol Abuse Treatment Services |

| - | IPV Perpetrator Intervention Programs |

| - | IPV-Victim Services |

| - | Legal-Aid |

| - | LGBT Pride Festivals |

| - | Mental Health Services |

| - | Multi-Site |

| - | National Telephone Survey |

| - | Online Market Research Panels |

| - | Online Media/Forums |

| - | Online Media/Forums - Colleges/Universities |

| - | Online Media/Forums - IPV-Victims |

| - | Online Media/Forums - LGBT |

| - | Online Media/Forums - Youth |

| - | Parent Education Services |

| - | Primary & Emer. Healthcare Services |

| - | Primary Schools |

| - | Print Media |

| - | Print Media - Colleges/Universities |

| - | Print Media - LGBT |

| - | Social Services |

| 5. Sampling Methods | Archival/Secondary Data |

| - | Convenience |

| - | Maximum Variation |

| - | Multi-Modal |

| - | Probability/Random |

| - | Purposive |

| - | Purposive-Probability |

| - | Random Digit Dialing |

| - | Snowball |

| - | Stratified Random |

| 6. Archival Data Source(s) | Client Records |

| - | Government-Sponsored Survey |

| - | Police/Court Records |

| 7. Research Design | Cross-Sectional |

| - | Experimental |

| - | Narrative |

| - | Phenomenological |

| - | Quasi-Experimental |

| 8. Experimental Design | Longitudinal |

| - | Pre-Test/Post-Test |

| - | RCT - Baseline + Follow-Up |

| - | RCT - Longitudinal |

| - | Vignette |

| 9. Quasi-Experimental Design | Quasi-Experimental Longitudinal |

| 10. Methodology | Meta-Analysis |

| - | Mixed-Methods |

| - | Not Applicable - Methodology |

| - | QuaLitative |

| - | QuaNTitative |

| - | Systematic Literature Review |

| 11. Mixed-Methods Resarch Design | Cross-Sectional |

| - | Experimental |

| - | Longitudinal |

| - | Pre-Test/Post-Test |

| 12. Mixed-Methods | 1-on-1 Interviews |

| - | Focus Groups |

| - | Multi-Modal |

| - | QuaLitative Survey |

| - | QuaNTitative Survey |

| 13. QuaLitative Research Design | Experimental |

| - | Longitudinal |

| - | Narrative |

| - | Phenomenological |

| 14. QuaLitative Methods | 1-on-1 Interviews |

| - | Archival/Secondary Data |

| - | Case Study |

| - | Focus Groups |

| - | Group Interviews |

| - | Multi-Modal |

| - | Participatory Observation |

| - | QuaLitative Survey |

| 15. QuaLitative Analytic Approaches | Constant Comparative Analysis |

| - | Content Analysis |

| - | Cross-Case Analysis |

| - | Descriptive |

| - | Grounded Theory |

| - | Grouped Thematic Analysis |

| - | Thematic Analysis |

| 16. QuaNTitative Research Design | Cross-Sectional |

| - | Experimental |

| - | Longitudinal |

| - | Pre-Test/Post-Test |

| - | Quasi-Experimental |

| 17. QuaNTitative Methods | 1-on-1 Interviews |

| - | Archival/Secondary Data |

| - | Multi-Modal |

| - | QuaNTitative Survey |

| 18. QuaNTitative Analytic Approaches | ANCOVA |

| - | ANOVA |

| - | Boostrapping |

| - | Chi-Square Difference Test |

| - | Chi-Square Goodness of Fit |

| - | Cluster Analysis |

| - | Confirmatory Factor Analysis (CFA) |

| - | Correlations |

| - | Descriptives |

| - | Exploratory Factor Analysis (EFA) |

| - | Factorial Invariance Testing Across Groups |

| - | Full SEM (Measurement + Structural Models) |

| - | Grounded Theory |

| - | Hierarchical Linear Regression |

| - | Indirect-Effects |

| - | Item Response Theory (IRT) |

| - | Latent Variable Modeling |

| - | Likelihood Ratio Tests (LRT) |

| - | Linear Regression |

| - | Logistic Regression |

| - | MANCOVA |

| - | MANOVA |

| - | Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) |

| - | Mediation |

| - | Mixed-Effects Modeling (MEM) |

| - | Moderation/Conditional Process |

| - | Multi-Group Modeling |

| - | Multi-Level Modeling (MLM) |

| - | Multivariate Analyses |

| - | Odds Ratios (OR) |

| - | Ordinary Least Squares Regression |

| - | Path Analysis |

| - | Post-Hoc Comparisons |

| - | Relative Risk Ratios (RRR) |

| - | Repeated-Measures ANOVA/ANCOVA |

| - | Step-Wise Regression |

| - | Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) |

| - | T-Test (Mean Differences) |

| - | Variance Adjusted Estimation |

| - | Weighted Least Squares (WLS) Estimation |

| 19. Ecological Level(s) of Analysis | Community |

| - | Exo-Macro |

| - | Individual |

| - | Meso-Exo |

| - | Micro |

| - | Relationship |

| - | Societal |

| 20. Exclude | Full Text Not Available |

| - | Non-Empricial |

| - | Non-US |

| - | Not SMW-Inclusive |

This document was created using R-v3.3.3 (R Core Team, 2016), and the following R-packages:

base-v3.3. (R Core Team, 2016), bibtex-v0.4. (Francois, 2014), cairoDevice-v2.24. (Lawrence, 2015), car-v2.1. (Fox & Weisberg, 2011), DBI-v0.7. (Databases, 2014), dplyr-v0.5. (Wickham & Francois, 2015), extrafont-v0.17. (Chang, 2014), ggplot2-v2.2. (Wickham, 2009), gWidgets-v0.0. (Verzani, 2014), gWidgetsRGtk2-v0.0. (Lawrence & Verzani, 2014), igraph-v1.0. (Csardi & Nepusz, 2006), knitr-v1.16. (Xie, 2015), pander-v0.6. (Daroczi & Tsegelskyi, 2015), plyr-v1.8. (Wickham, 2011), RGtk2-v2.20. (Lawrence & Temple Lang, 2010), rmarkdown-v1.5. (J. Allaire et al., 2016), RQDA-v0.2. (Huang, 2014), RSQLite-v1.0. (Wickham, James, & Falcon, 2014), scales-v0.4. (Wickham, 2016a), tidyr-v0.6. (Wickham, 2016b), ggthemes-v3.4. (Arnold, 2016), kableExtra-v0.2. (Zhu, 2016), tufte-v0.2. (Xie & Allaire, 2016), devtools-v1.13. (Wickham & Chang, 2016), sysfonts-v0.5. (Qiu & others, 2015), showtext-v0.4. (Qiu, 2015), Riley-v0.1. (Smith-Hunter, 2017), and stats-v3.3. (Team & worldwide, 2017)

Allaire, J., Cheng, J., Xie, Y., McPherson, J., Chang, W., Allen, J., … Hyndman, R. (2016). rmarkdown: Dynamic documents for R. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=rmarkdown

Arnold, J. B. (2016). ggthemes: Extra themes, scales and geoms for ggplot2. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ggthemes

Chang, W. (2014). extrafont: Tools for using fonts. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=extrafont

Csardi, G., & Nepusz, T. (2006). The igraph software package for complex network research. Interjournal, Complex Systems, 1695. Retrieved from http://igraph.org

Daroczi, G., & Tsegelskyi, R. (2015). pander: An R pandoc writer. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=pander

Databases, R. S. I. G. on. (2014). DBI: RDatabase interface. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=DBI

Edelen, M. O., McCaffrey, D. F., Marshall, G. N., & Jaycox, L. H. (2009). Measurement of teen dating violence attitudes an item response theory evaluation of differential item functioning according to gender. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 24(8), 1243–1263.

Fox, J., & Weisberg, S. (2011). An R companion to applied regression (Second). Thousand Oaks CA: SAGE. Retrieved from http://socserv.socsci.mcmaster.ca/jfox/Books/Companion

Francois, R. (2014). bibtex: Bibtex parser. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=bibtex

Fryer, D. (2008). Some questions about “the history of community psychology”. Journal of Community Psychology, 36(5), 572–586.

Higgins, J., & Green, S. (Eds.). (2011). Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 5.1.0 [updated march 2011]. London, UK: The Cochrane Collaboration. Retrieved from http://handbook.cochrane.org

Huang, R. (2014). RQDA: R-based qualitative data analysis. Retrieved from http://rqda.r-forge.r-project.org/

Lawrence, M. (2015). cairoDevice: Embeddable cairo graphics device driver. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=cairoDevice

Lawrence, M., & Temple Lang, D. (2010). RGtk2: A graphical user interface toolkit for R. Journal of Statistical Software, 37(8), 1–52. Retrieved from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v37/i08/

Lawrence, M., & Verzani, J. (2014). gWidgetsRGtk2: Toolkit implementation of gWidgets for RGtk2. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gWidgetsRGtk2

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative data analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22(4), 557.

Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., Altman, D. G., & The PRISMA Group. (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. PLoS med, 6(7), e1000097. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., & Weinbaum, R. K. (2017). A framework for using qualitative comparative analysis for the review of the literature. The Qualitative Report, 22(2), 359–372.

Onwuegbuzie, A. J., Dickinson, W. B., Leech, N. L., & Zoran, A. G. (2009). A qualitative framework for collecting and analyzing data in focus group research. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 8(3), 1–21.

Qiu, Y. (2015). showtext: Using fonts more easily in RGraphs. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=showtext

Qiu, Y., & others. (2015). sysfonts: Loading system fonts into R. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=sysfonts

R Core Team. (2016). R: A language and environment for statistical computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing. Retrieved from https://www.R-project.org/

Smith-Hunter, R. (2017). Riley: A developing package of r functions for (community-based) psychology research. Retrieved from https://github.com/EccRiley/Riley

Team, R. C., & worldwide. (2017). The R stats package. Retrieved from http://www.r-project.org/

The Society for Community Research and Action (SCRA). (2017). Other journals relevant to community psychology. Retrieved from http://www.scra27.org/publications/other-journals-relevant-community-psychology/

Verzani, J. (2014). GWidgets: GWidgets API for building toolkit-independent, interactive GUIs. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=gWidgets

Wickham, H. (2009). ggplot2: Elegant graphics for data analysis. Springer-Verlag New York. Retrieved from http://ggplot2.org

Wickham, H. (2011). The split-apply-combine strategy for data analysis. Journal of Statistical Software, 40(1), 1–29. Retrieved from http://www.jstatsoft.org/v40/i01/

Wickham, H. (2016a). scales: Scale functions for visualization. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=scales

Wickham, H. (2016b). tidyr: Easily tidy data with spread() and gather() functions. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tidyr

Wickham, H., & Chang, W. (2016). devtools: Tools to make developing RPackages easier. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=devtools

Wickham, H., & Francois, R. (2015). dplyr: A grammar of data manipulation. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=dplyr

Wickham, H., James, D. A., & Falcon, S. (2014). RSQLite: SQLite interface for R. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=RSQLite

Witte, T. H., Mulla, M. M., & Weaver, A. A. (2015). Perceived social norms for intimate partner violence in proximal and distal groups. Violence and Victims, 30(4), 691–698.

Xie, Y. (2015). Dynamic documents with R and knitr (2nd ed.). Boca Raton, Florida: Chapman; Hall/CRC. Retrieved from http://yihui.name/knitr/

Xie, Y., & Allaire, J. (2016). tufte: Tufte’s styles for Rmarkdown documents. Retrieved from https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=tufte

Zhu, H. (2016). kableExtra: Decorate kable output using pipe syntax. Retrieved from https://github.com/haozhu233/kableExtra

Tufte CSS theme by Dave Liepmann & Edward Tufte